This guide takes a more "mathematical" and "rigorous" approach, for those who care enough about the math behind it all.

This guide is specifically directed towards habitable worlds, but the same concepts apply to any world.

Unless you want a dead, dark rock for a planet, you're gonna need a star.

Since we want to make a habitable world, we need a star at least as hot as the Earth. Otherwise, how is the planet supposed to get hotter than the star? Thankfully, even brown dwarfs can generate this kind of relatively low heat. The only other feature we'll have to look out for is the Roche limit. Even if our star generates enough heat, the planet'll get torn to shreds if we place it too close. So, for our rough "bare minimum" mass, the temperature at the Roche limit has to be at least that of Earth. At this point, we just set the Roche and heat equations equal to each other...

$$a = R_M \sqrt[3]{2 \frac {\rho_M} {\rho_m}}$$ $$T_{eq} = T_{star} \sqrt{\frac {R_M}{2a}} \sqrt[4]{1-A}$$Unfortunately, since the heat equation is solved for \({ T }_{ eq }\), we need to solve for \(a\):

$$a = \frac {T_{star}^2 R_M}{2T_{eq}^2} \sqrt { 1-A }$$Now we're in business.

$$R_M \sqrt[3]{2 \frac {\rho_M} {\rho_m}} = \frac {T_{star}^2 R_M}{2T_{eq}^2} \sqrt { 1-A }$$We can cancel out the star's radii for starters:

$$ \sqrt[3]{2 \frac {\rho_M} {\rho_m}} = \frac {T_{star}^2}{2T_{eq}^2} \sqrt { 1-A }$$It might look like we can't cancel out anything else, but actually, we can. Since we're finding the bare minimum, we can assume the planetary albedo is zero, since that's as efficient a planet can get at absorbing light.

$$ \sqrt[3]{2 \frac {\rho_M} {\rho_m}} = \frac {T_{star}^2}{2T_{eq}^2}$$There's a very handy rule of thumb when it comes to stellar temperatures, and it ends up being rather accurate:

$$ T_{star} = T_\odot \sqrt{\frac {M_{star}} {M_\odot}}$$This alone won't help us though. We'll also need a formula to get density. Thankfully, there's also another helpful approximation!

$$ R_{star} = R_\odot \frac {M_{star}} {M_\odot}$$Let's plug this into the density equation:

$$ \rho = \frac {m} {\frac {4} {3} \pi r^3}$$ $$ \rho_{star} = \frac {M_{star}} {\frac {4} {3} \pi \left( R_\odot \frac {M_{star}} {M_\odot} \right) ^3}$$ $$ \rho_{star} = \frac {3 M_\odot^3} {4 \pi R_\odot^3 M_{star}^2}$$Let's chuck it all back into the big equation, simplify, and isolate \(M_M\):

$$ \sqrt[3]{2 \frac {\frac {3 M_\odot^3} {4 \pi R_\odot^3 M_M^2}} {\rho_m}} = \frac {T_\odot^2 \frac {M_M} {M_\odot}}{2T_{eq}^2}$$ $$ \frac {12 M_\odot^5} {\pi R_\odot^3 \rho_m} = \frac {T_\odot^6 M_M^4}{T_{eq}^6}$$ $$ M_M^4 = \frac {12 M_\odot^5 T_{eq}^6} {\pi R_\odot^3 \rho_m T_\odot^6}$$This is great! Don't let all the symbols fool you, the only unknowns at this point are \(\rho_m\) and \(M_M\). The equilibrium temperature is going to be Earth's (~255K). Since it's clear that higher densities allow for a smaller minimum, we can assume the density is equivalent to the densest planet in the solar system - Earth! Now, we just have to plug this formula into a calculator!

$$ M_M = \sqrt[4] {\frac {12 M_\odot^5 T_{eq\oplus}^6} {\pi R_\odot^3 \rho_\oplus T_\odot^6}}$$ $$ M_M = 2.523 \cdot 10^{28} \mathrm{kg} = 13.29M_J$$So it seems all but the smallest brown dwarfs can safely hold a planet with similar temperature to Earth. In practice though, our planet's gonna have albedo. With an earthlike albedo, this actually becomes:

$$ M_M = 5.009 \cdot 10^{28} \mathrm{kg} = 26.39M_J$$And if our planet didn't have a greenhouse effect, that would increase even more to:

$$ M_M = 6.249 \cdot 10^{28} \mathrm{kg} = 32.92M_J$$As long as we're above these values, we're safe, at least in terms of temperature. A problem with this brown dwarf world arises when you calculate the peak emission wavelength: (via Wien's displacement law, \(b\) is a constant which has a page on NIST detailing its value)

$$ \lambda = \frac {b} {T}$$ $$ \lambda = 3.254 \mathrm{\mu m}$$This is in the infrared range, and so our brown dwarf would appear very dim to our eyes, as the upper limit of human vision is about \(740 \mathrm{nm}\). Perhaps though, this world has evolved critters with IR vision - who knows! There are other hypothetical issues with brown dwarfs, including tidal locking, but nothing explicitly precluding the appearance of life.

Red dwarfs are the most common type of main sequence star in the universe, accounting for three-quarters of all main sequence stars. Only one potential issue exists: tidal locking. Life can certainly exist on a tidally locked world, but it may be very difficult. The timeframe for tidal locking to occur is roughly:

$$ t_{lock} \approx \frac {a^6 r} {mM^2} \cdot 5\cdot10^{28} \mathrm{\frac {kg^3 s} {m^7}}$$For an earthlike world, this simplifies to:

$$ t_{lock} \approx \frac {a^6} {M^2} \cdot 5\cdot10^{10} \mathrm{\frac {kg^2 s} {m^6}}$$If we want enough time for life to evolve, we're gonna need \(t_{lock}\) to equal the age of the earth:

$$ 1.43\cdot10^{17} \mathrm{s} \approx \frac {a^6} {M^2} \cdot 5\cdot10^{10} \mathrm{\frac {kg^2 s} {m^6}}$$ $$ a^6 \approx M^2 \cdot 2.69\cdot10^{6} \mathrm{\frac {m^6} {kg^2}}$$ $$ a \approx 11.8 \sqrt[3]{M} \mathrm{\frac {m} {kg^{\frac{1}{3}}}}$$For the smallest red dwarfs \(M=0.08M_\odot\), this distance is about \(a=0.427\mathrm{au}\). However, given the star property approximations mentioned in the last section, a planet orbiting at this distance would have a temperature of just \(T_{eq}=29\mathrm{K}\). So clearly, if we care about tidal locking, we're gonna have to figure out the minimum mass which allows a world to exist safely. Again, since this is a minimum, we can assume albedo is optimal:

$$ 11.8 \sqrt[3]{M} \mathrm{\frac {m} {kg^{\frac{1}{3}}}} = \frac {T_{star}^2 R}{2T_{eq}^2}$$Using the approximation for \(R\) and \(T_{star}\), and simplifying:

$$ 11.8 \sqrt[3]{M} \mathrm{\frac {m} {kg^{\frac{1}{3}}}} = \frac {T_\odot^2 R_\odot M^2}{2T_{eq}^2 M_\odot^2}$$ $$ 23.6 \mathrm{\frac {m} {kg^{\frac{1}{3}}}} = \frac {T_\odot^2 R_\odot M^{\frac{5}{3}}}{T_{eq}^2 M_\odot^2}$$Isolate M, and solve:

$$ M^{\frac{5}{3}} = \frac {T_{eq}^2 M_\odot^2}{T_\odot^2 R_\odot } \cdot 23.6 \mathrm{\frac {m} {kg^{\frac{1}{3}}}}$$ $$ M = 1.779 \cdot 10^{30} \mathrm{kg} = 0.8948M_\odot$$A star of this mass would be of type G7V. But wait, don't put your red and orange dwarfs down yet! If our world is a moon orbiting a gas giant, none of this even matters! And if you don't care about tidal locking, or have a shorter timeframe, you can also ignore this.

Having a yellow dwarf is definitely the most conservative way to go. After all, if we sprung from a rock orbiting one yellow dwarf, surely there must be others! Indeed, that is the case. You don't need to worry about anything with this class, so let's move on to the next.

Now we get into the big stars. The big issue here is, again, the timeframe. But this time, instead of worrying about tidal locking, we have to worry about the lifespan of the star. A good approximation for lifespan is given by:

$$ t_{star} = t_\odot \sqrt{\frac {M_\odot^5}{M_{star}^5}}$$Since we want the lifespan to be at least the age of the Earth, we just have to rearrange this equation and solve:

$$ M_{star} = M_\odot \sqrt[5] {\frac {t_\odot^2}{t_{\oplus}^2}}$$ $$ M_{star} = 2.727 \cdot 10^{30} \mathrm{kg} = 1.371M_\odot$$You can see how much impact adding just a little mass makes. In fact, if we were to just throw Jupiter into the sun, it'd reduce the sun's lifespan by almost twenty-three million years! The earliest known life appeared on earth about 4.28 Bya, which means simple life could arise in just 260 million years. If we plug this value in instead, we get this:

$$ M_{star} = 8.561 \cdot 10^{30} \mathrm{kg} = 4.305M_\odot$$Consider the first value to be the most conservative upper limit, and the second value to be the most liberal upper limit. A star of the former mass would be of type F4V and the latter mass would be of type B7V.

Now we get into the meat of worldbuilding. If you don't care about scientific plausibility (why are you even reading this, then?), skip ahead to the summary. Otherwise...

Terran life is on land and in the sea. Some creatures also take flight, but must always rest on land. All of the following theoretical constraints are for earthlike life. Before the summary, however, I go briefly into other types of life.

The first thing we need to get into is the physical features, because there is one thing specifically many authors cite as problematic: surface gravity. If it's too high, or too low, us frail little humans are gonna either go splat, or get atrophied muscles. I once read somewhere that the safe minimum for long duration is 0.3g, and GLOC (blackout) occurs as low as 4g. I have no idea where these numbers come from. As far as I can tell, these numbers have been passed down from generation to generation since the dawn of time. So far, we have this:

$$ 0.3g_\oplus < g_p < 4g_\oplus $$This is good, but unfortunately useless unless we get some way to relate mass to radius. Oh wait, that's right! If we know the density, we can relate the mass to the radius! Note that for the rocky planets of our solar system, the density varies between:

$$ 3934 \mathrm{\frac {kg}{m^3}} < \rho < 5514 \mathrm{\frac {kg}{m^3}} $$Recall the density and surface gravity formulas:

$$ \rho = \frac {M}{\frac{4}{3} \pi r^3} $$ $$ g = \frac {GM}{r^2}$$ $$ 3934 \mathrm{\frac {kg}{m^3}} < \frac {M}{\frac{4}{3} \pi r^3} < 5514 \mathrm{\frac {kg}{m^3}} $$Let's solve for the lower bound on mass:

$$ \frac {M}{\frac{4}{3} \pi r^3} < 5514 \mathrm{\frac {kg}{m^3}} $$ $$ \frac {M}{r^3} < 2.310 \cdot 10^4 \mathrm{\frac {kg}{m^3}} $$ $$ r^3 > M \cdot 4.330 \cdot 10^{-5} \mathrm{\frac {m^3}{kg}} $$ $$ r > \sqrt[3] {M} \cdot 3.511 \cdot 10^{-2} \mathrm{\frac {m}{\sqrt[3]{kg}}} $$ $$ g < \frac {GM}{\sqrt[3] {M^2} \cdot 1.233 \cdot 10^{-3} \mathrm{\frac {m^2}{\sqrt[3]{kg^2}}}}$$ $$ g < \frac {G \sqrt[3]{M}}{1.233 \cdot 10^{-3} \mathrm{\frac {m^2}{\sqrt[3]{kg^2}}}}$$ $$ g < \sqrt[3]{M} \cdot 5.413 \cdot 10^{-8} \mathrm{\frac {m}{s^2 \sqrt[3]{kg}}}$$ $$ 0.3g_\oplus < \sqrt[3]{M} \cdot 5.413 \cdot 10^{-8} \mathrm{\frac {m}{s^2 \sqrt[3]{kg}}}$$ $$ 5.431 \cdot 10^7 < \sqrt[3]{M} \mathrm{\frac {1}{\sqrt[3]{kg}}}$$ $$ M > 1.602 \cdot 10^{23} \mathrm{kg} = 0.02682 M_\oplus$$And the upper bound:

$$ 3934 \mathrm{\frac {kg}{m^3}} < \frac {M}{\frac{4}{3} \pi r^3} $$ $$ 1.648 \cdot 10^4 \mathrm{\frac {kg}{m^3}} < \frac {M}{r^3} $$ $$ r^3 < M \cdot 6.068 \cdot 10^{-5} \mathrm{\frac {m^3}{kg}} $$ $$ r < \sqrt[3]{M} \cdot 3.930 \cdot 10^{-2} \mathrm{\frac {m}{\sqrt[3]{kg}}} $$ $$ g > \frac {GM}{\sqrt[3]{M^2} \cdot 1.544 \cdot 10^{-3} \mathrm{\frac {m^2}{\sqrt[3]{kg^2}}}}$$ $$ g > \frac {G \sqrt[3]{M}}{1.544 \cdot 10^{-3} \mathrm{\frac {m^2}{\sqrt[3]{kg^2}}}}$$ $$ g > \sqrt[3]{M} \cdot 4.322 \cdot 10^{-8} \mathrm{\frac {m}{s^2 \sqrt[3]{kg}}}$$ $$ 4g_\oplus > \sqrt[3]{M} \cdot 4.322 \cdot 10^{-8} \mathrm{\frac {m}{s^2 \sqrt[3]{kg}}}$$ $$ 9.089 \cdot 10^8 > \sqrt[3]{M} \mathrm{\frac {1}{\sqrt[3]{kg}}}$$ $$ M < 7.057 \cdot 10^{26} \mathrm{kg} = 125.7 M_\oplus$$However, the lower limit for gas giants is about \(10M_\oplus\), so you hit a different (atmospheric!) roadblock long before having to worry about surface gravity. Note that the lower bound is about half Mercury's mass. Indeed, Mercury's surface gravity is only about 0.4g, just over our lower limit on surface gravity. Aside from surface gravity, there is the issue of having a thick enough atmosphere to retain an atmosphere. If the life is under a subterranean ocean a la Europa, this won't be an issue. For most worlds, however, this is significant. Atmosphere loss is caused by the excitation of individual air molecules, ie., their velocity. This is determined primarily by temperature and molar mass. As long as this excitation is less than the escape velocity, the molecules are retained. This is why the rocky planets don't have hydrogen and helium in their atmospheres in significant quantities. Earth would need to be either more massive (~3x) or colder (~100K). I've never been able to find an actual formula from a decent source, but through trial and error I've developed this equation which gives a good approximation of the minimum escape velocity needed to contain a molecule:

$$ v_e = \frac {T} {\sqrt {M}} \cdot 50 \mathrm{\frac {m} {s}}$$Where T is given in Kelvins and M is given in g/mol. Most if not all life on Earth needs either oxygen or carbon dioxide to live. Since oxygen has a lower molar mass, it would escape first, and so using O2 yields a harder limit than using CO2:

$$ v_e = T \cdot 8.839 \mathrm{\frac {m} {sK}}$$Since the surface temperature is presumably analogous to Earth's, that's another variable taken care of:

$$ v_e = 2546 \mathrm{\frac {m} {s}}$$So our planet needs an escape velocity greater than this. We need to find the smallest mass such that, even with the maximum density, our escape velocity is just barely this. Recall from before:

$$ r = \sqrt[3] {M} \cdot 3.511 \cdot 10^{-2} \mathrm{\frac {m}{\sqrt[3]{kg}}} $$Now, to solve the escape velocity formula for r:

$$ v_e = \sqrt {\frac {2GM} {r}} $$ $$ r = \frac {2GM} {v_e^2} $$Set them equal, and solve:

$$ \frac {2GM} {v_e^2} = \sqrt[3] {M} \cdot 3.511 \cdot 10^{-2} \mathrm{\frac {m}{\sqrt[3]{kg}}} $$ $$ G \sqrt[3] {M^2} = 1.138 \cdot 10^5 \mathrm{\frac {m^3}{s^2\sqrt[3]{kg}}} $$ $$ \sqrt[3] {M^2} = 1.705 \cdot 10^{15} \mathrm{\sqrt[3]{kg^2}} $$ $$ M = 7.040 \cdot 10^{22} \mathrm{kg} = 0.01179M_\oplus$$Hah! Note that this is even lower than our previous lower bound. In fact, this is only about one-fifth the mass of Mercury. So why doesn't Mercury have an atmosphere, you may ask? Because it's must hotter than the Earth, so the escape velocity requirement for O2 would be:

$$ v_e = 6187 \mathrm{\frac {m} {s}}$$However, Mercury's escape velocity is only:

$$ v_e = 4250 \mathrm{\frac {m} {s}}$$So can't retain molecular oxygen like Venus and Earth can - it only has a very tenuous atmosphere, with a surface pressure of a mere 0.5 nPa! This means the mass of the entire atmosphere is only about 10 t.

Dwarf planets are unable to contain life (at least, any simpler than bacteria), so knowing the limit here between a planet and dwarf planet may be good. There are three criteria for a body to be a planet:

The first easy to check. The other two... not so much. The least massive known gravitationally-rounded object in the solar system is Orcus, so we can let that be our minimum:

$$ M > 6.41 \cdot 10^{20} \mathrm{kg} = 107 \mu M_\oplus$$There's a very good metric for estimating whether or not something is a planet, called Margot's planetary discriminant (Π). Values of Π over 1 indicate a planet.

$$ 1 < \frac {807\frac{m}{M_\oplus}} {\left(\frac{M}{M_\odot}\right)^{\frac{5}{2}} \left(\frac{a}{\mathrm{au}}\right)^{\frac{9}{8}}} $$ $$ \left(\frac{M}{M_\odot}\right)^{\frac{5}{2}} \left(\frac{a}{\mathrm{au}}\right)^{\frac{9}{8}} < 807\frac{m}{M_\oplus} $$We know we can derive semimajor axis from the distance since we're concerned with worlds in the habitable zone. There's a very clean formula for this:

$$ a = \sqrt{\frac {L_{star}} {L_\odot}} \mathrm{au}$$There's also a good approximation for luminosity for main-sequence stars:

$$ L_{star} = L_\odot \left( \frac {M_{star}}{M_\odot} \right)^{\frac{7}{2}} $$Combine these two:

$$ a = \left( \frac {M_{star}}{M_\odot} \right)^{\frac{7}{4}} \mathrm{au}$$Plug it in:

$$ \left(\frac{M}{M_\odot}\right)^{\frac{5}{2}} \left(\frac{\left( \frac {M}{M_\odot} \right)^{\frac{7}{4}} \mathrm{au}}{\mathrm{au}}\right)^{\frac{9}{8}} < 807\frac{m}{M_\oplus} $$ $$ \left(\frac{M}{M_\odot}\right)^{\frac{5}{2}} \left(\left( \frac {M}{M_\odot} \right)^{\frac{7}{4}}\right)^{\frac{9}{8}} < 807\frac{m}{M_\oplus} $$ $$ \left(\frac{M}{M_\odot}\right)^{\frac{143}{32}} < 807\frac{m}{M_\oplus} $$ $$ 2.970 \cdot 10^{-114}\mathrm{kg^{\frac{-111}{32}}} \cdot M^{\frac{143}{32}}< m $$We can now find the lowest stellar mass where this constraint even matters to us:

$$ 2.970 \cdot 10^{-114}\mathrm{kg^{\frac{-111}{32}}} \cdot M^{\frac{143}{32}}< 0.02682M_\oplus $$ $$ M < 3.957 \cdot 10^{30} \mathrm{kg} = 1.990M_\odot$$We can also find the lowest stellar mass where even the largest rocky planets can't form in the habitable zone:

$$ 2.970 \cdot 10^{-114}\mathrm{kg^{\frac{-111}{32}}} \cdot M^{\frac{143}{32}}< 10M_\oplus $$ $$ M < 1.488 \cdot 10^{31} \mathrm{kg} = 7.486M_\odot$$So earthlike planets orbiting stars under 2 solar masses don't really need to worry about formation difficulties. These same planets between 2 and 7 solar masses might have to worry, depending on their mass. Above 7 solar masses, there's no hope of an earthlike planet. You'd have to have an earthlike moon orbiting a gas giant, or something. Overall though, this criterion doesn't really place any kind of constraint on mass.

There is one situation where none of the above criteria matter: subterranean oceans. Numerous moons in our own solar system are widely thought to have these: most famously, Europa and Enceladus. The former has even been the basis for quite a few books and films, including Europa Report. A few other satellites have also been more recently hypothesized to contain subterranean oceans too, including Ganymede and Triton. The only concern here is that photosynthesis would be impossible, but plenty of Earth life lives without that, anyways.

In addition, there are several proposed alternate biochemical bases, ranging from different solvents (methane, ammonia, ...), to totally different bases like silicon-based life. I have absolutely no idea whatsoever as to what this life would look like, and I doubt anyone else does, either. I'm no biologist, so I have no idea how credible any of these are, but in terms of the physics of the planet...

(Before I start, one caveat. The problem with these phase calculations is most information available assumes pressure is similar to Earth's. At higher pressures (but much higher than Earth's), these can exist in liquid phase at terran temperatures. I haven't been able to find particularly good phase diagrams for either, and anyways, the calculations with pressure taken into account are even more complex. So, unfortunately, I have made these same assumptions here. Just hope your atmosphere is similar to Earth's...)

Life using ammonia as a solvent would likely require it to be at a similar "distance" after its melting point as terrans need water. That would put the ideal temperature at about 212K, only two degrees above Mars' mean temperature! If Mars had more ammonia, perhaps we'd see life on Mars...

Similar logic would put the ideal temperature for methane at about 94K, moving the habitable zone to just slightly beyond Jupiter's orbit. Or, if the planet has a decent greenhouse effect like Titan (which has methane lakes, by the way!), around Saturn. Perhaps when the Dragonfly lander arrives on Titan in 2036, we'll discover such life. Perhaps.

I've also seen this. I include it because it's only of the only two proposed solvents (aside from sulfuric acid) liquid at STP like water. Life with this base might feel most comfortable at temperatures around 352K. Sulfuric Acid peeps might enjoy temperatures of 412K, but maybe even temperatures over 500K!

Note that the upper limit is just the approximate boundary between a rocky and gas planet. Doubling the mass of a planet but keeping the density the same only increases the surface gravity by 26%, so a planet at that boundary would only have a surface gravity of about 2.154g. It would be difficult for humans to stand, but other lifeforms might not have as much difficulty, but with a low density that could be reduced to just 1.539g.

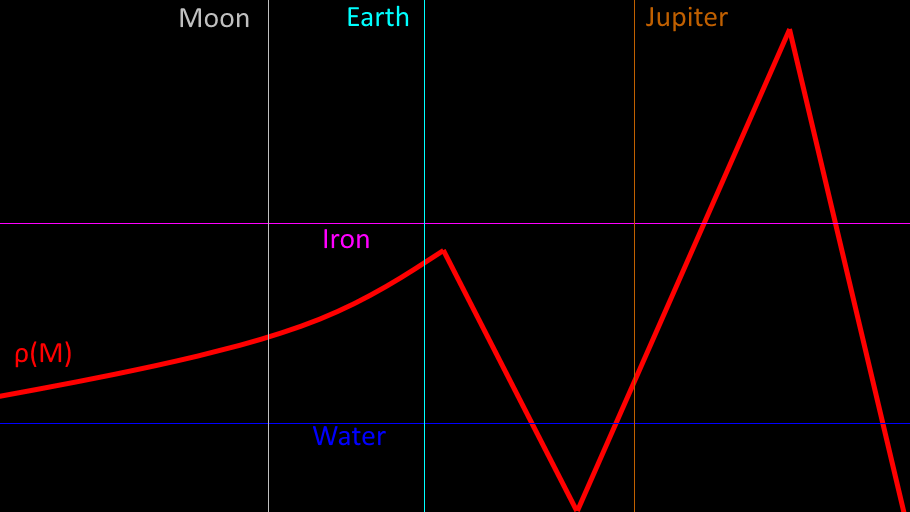

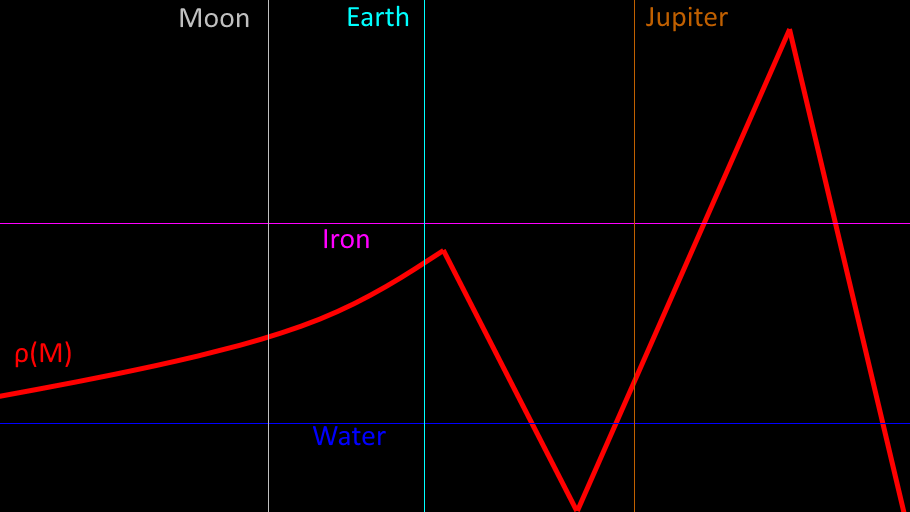

There are four "trends" in body formation, based on exoplanet data. If you log-log plot these, they look more or less like flat lines.

Which then decreases, presumably due to gas accumulation, to:

$$ → (4.4 \cdot 10^{26} \mathrm{kg}, 670 \mathrm{\frac {kg} {m^3}})$$But then increases again, as the radius approaches Jupiter's, and becomes denser until it is a class M star:

$$ → (1.5 \cdot 10^{29} \mathrm{kg}, 180000 \mathrm{\frac {kg} {m^3}})$$And finally decreases again, forever, as mass continues to pile on:

$$ → (1.4 \cdot 10^{32} \mathrm{kg}, 0.49 \mathrm{\frac {kg} {m^3}})$$We can do a linear regression on the log-log plot to get the following piecewise function:

$$ \rho(M) \approx \begin{cases} 5.0M^{0.13} & \mbox{if } M \lt 1 \cdot 10^{25} \mathrm{kg} \\ 4.1 \cdot 10^{19} M^{-0.63} & \mbox{if } 1 \cdot 10^{25} \mathrm{kg} \le M \lt 4.4 \cdot 10^{26} \mathrm{kg} \\ 1.8 \cdot 10^{-23} M^{0.96} & \mbox{if } 4.4 \cdot 10^{26} \mathrm{kg} \le M \lt 1.5 \cdot 10^{29} \mathrm{kg} \\ 5.9 \cdot 10^{60} M^{-1.9} & \mbox{if } 1.5 \cdot 10^{29} \mathrm{kg} \le M \end{cases} $$This isn't a particularly good approximation, but it works for our purposes here.

$$ M(\rho) \approx \begin{cases} 4.0 \cdot 10^{-6} \rho^{7.7} & \mbox{if } \rho \lt 7200 \mathrm{\frac {kg} {m^3}} \\ 1.8 \cdot 10^{31} \rho^{-1.6} & \mbox{if } 670 \mathrm{\frac {kg} {m^3}} \lt \rho \lt 7200 \mathrm{\frac {kg} {m^3}} \\ 5.3 \cdot 10^{23} \rho^{1.0} & \mbox{if } 670 \mathrm{\frac {kg} {m^3}} \lt \rho \lt 180000 \mathrm{\frac {kg} {m^3}} \\ 2.7 \cdot 10^{32} \rho^{-0.53} & \mbox{if } \rho \lt 180000 \mathrm{\frac {kg} {m^3}} \end{cases} $$So with the density of water (1000 kg/m3), we get:

$$ M(\rho_{water}) \approx \begin{cases} 5.0 \cdot 10^{17} \mathrm{kg} \\ 2.9 \cdot 10^{26} \mathrm{kg} = 49M_\oplus\\ 5.3 \cdot 10^{26} \mathrm{kg} = 89M_\oplus \\ 6.9 \cdot 10^{30} \mathrm{kg} = 3.5M_\odot \end{cases} $$Which is slightly off (I might've made a mistake somewhere), but you get the idea...

_flatten_crop.jpg/240px-Neptune_-_Voyager_2_(29347980845)_flatten_crop.jpg)

Experimentally, in SpaceEngine, with the following parameters:

The following statistics are noted per system:

Experimentally, in SpaceEngine, with the following parameters:

The following statistics are noted per system: